Andebit et beaqui corendit, ut quostes esciendion re dit ad et prae parion es quia quas alibus sam, omnim faciden ducipidiat arum autem nobis enis es voat

General John Burgoyne Arrives on the World Stage

The course and outcome of the 1777 campaign were largely determined by the experience and ambition of one man: Lieutenant General John Burgoyne.

Born to mother Anna Maria and Captain John Burgoyne in 1722, young John Burgoyne was afforded many advantages as a child. In 1731, his Godfather Lord Bingley died with no heirs and left nine-year-old Burgoyne a handsome legacy. As a result of the inheritance, which jumpstarted the young man’s career, rumors stirred about the legitimacy of the young boy’s birth. The next year, Burgoyne was enlisted in the prestigious Westminster School, which many aspiring military officers attended.

By 15, Burgoyne had purchased an officer’s commission in a fashionable cavalry regiment stationed in London. His duties were light, allowing him time to mingle with the London elite. Burgoyne became known for his fashionable appearance and high living, which led historians to dub him “Gentleman Johnny.” But he was living beyond his means and eventually had to sell his commission to pay off his accumulated debts. Burgoyne was down on his luck, but renewed conflict in Europe would soon afford the young man another opportunity.

The War for Austrian Succession (1740-1748) was the result of a power struggle to maintain the balance of power in Europe. In 1740, King Frederick II of Prussia, also known as Frederick the Great, violated an agreement to allow Maria Theresa to ascend to the throne after the death of her father, Holy Roman Emperor Charles VI. Frederick invaded Austria, supported by France and Spain; while Great Britain sided with Maria Theresa of Austria. With extended warfare on the continent, Britain’s standing army was expanded and new regiments formed.

In 1745, Burgoyne enlisted in the 1st Royal Dragoons, a light cavalry unit, and was given a commission as Cornet, the lowest grade of commissioned officer in the British cavalry. Since the unit was newly created, he did not need to pay a commission. Burgoyne quickly ascended the ranks. First he was promoted to lieutenant and within two years he managed to purchase a captaincy. He was eager for further advancement, but the end of the war in 1748 brought an end to future prospects.

Upon his return to the London social scene, he became enamored with Lady Charlotte Stanley, daughter of the Earl of Derby. The Stanleys were landed aristocracy, so when Burgoyne, who was of low or illegitimate birth, asked Derby for his daughter’s hand in marriage, he refused. Unwilling to be swayed by Derby’s refusal, Burgoyne sold his commission again, eloped with Charlotte, and moved to France. It was not until daughter Charlotte Elizabeth was born in 1754 that Derby reconciled with John and Charlotte. After a short period, John and Derby became close and Derby used his influence to boost his son-in-law’s prospects just as a new war was emerging in Europe—a global conflict known as the Seven Years War.

Thanks to his connection with Derby, Burgoyne was able to purchase a commission in the 11th dragoons just one month after the start of the war. He participated in several expeditions, proving his leadership ability and ascending to the rank of brigadier general. Burgoyne stood out from the British military leadership by revolutionizing recruitment techniques, insisting that his troops be treated with humanity and that they learned military sciences so they could think and act independently during battle. He received distinctions for the Raid of St. Malo on the French coast in 1758 and for helping ward off the Spanish Invasion of Portugal in 1762.

At the end of the Seven Years War, when peace resumed, Burgoyne occupied himself with the luxuries of London nobility. In 1768, he was elected to the House of Commons. He gained notoriety in 1772 when he led a campaign against corruption in the East Indian Company. He also became a playwright. He wrote The Maid of Oaks, which was produced by the famed actor, manager, and producer David Garrick in 1775. When the unruly Rebel colonists caused an uprising, he was promoted to Major General and sent to America.

Burgoyne was dispatched to support General Gage at Boston but was third in command under Generals William Howe and Henry Clinton. He was present during the costly Battle of Bunker Hill, but his primary responsibility was to draft proclamations, which were long-winded and ridiculed by both British and American contemporaries. Frustrated by the lack of opportunities, he returned to England, where he petitioned for a command.

In the summer of 1776, the British launched a three-pronged attack on the Rebel colonies, one of which Burgoyne led: Burgoyne was dispatched to Quebec in April 1776 and helped General Guy Carlton drive out Benedict Arnold and the Rebels from Canada. Burgoyne, who was supposed to continue the campaign, instead returned home to see to the burial of his beloved wife Charlotte in October 1776. Thus, Carleton was put in charge. He constructed a navy on Lake Champlain and launched an attack on Lake Champlain, but failed to secure Fort Ticonderoga before winter.

You will not wonder, my dear friend, at my return to England—a secondary station in a secondary army is at no times agreeable; but many circumstances combine to render it in the present instance uncommonly dissatisfactory. My private [thoughts] are yet more forcible—a mind sunk at time in distress, a constitution unfitted to severity of cold, a few duties yet remaining to the memory of Lady Charlotte, compel me to break through the bars of ice & snow which are forming to seclude this country from the rest of the globe for the next six months. I mean not however to withdraw myself from the American War unless French one breaks out—an uncommitted cipher in the world — the portion lost which made prosperity an object of solicitude—my prospects are closed – Interest, ambition of life is over. Profession & honour is all that remains, & I would rather than finished in a professional grave, than to slow wasting, decrepitude & infirmness of the age. —John Burgoyne to Sir Henry Clinton, November 7, 1776

Burgoyne was not idle for long. In anticipation of the 1777 campaign season, he devised a plan called “Thoughts for Conducting War from the Side of Canada.” On the first day of the new year, Burgoyne wrote Lord George Germaine, Secretary of State for the Colonies, in order to impress him with his ambitions for that year’s campaign. Germaine had the great responsibility of promoting or relieving Generals, taking care of provisions and supplies and the strategic planning of the war.”

Letter from John Burgoyne to Lord George Germaine, Jan 1, 1777:

“My Lord,

My Physician has pressed me to go to Bath for a short time & I find it requisite to my health & spirits to follow his advice— But I think it a previous duty to assure your Lordship, that should my attendance in Town become necessary relatively to information upon the affairs of Canada, I shall be ready to obey your summons upon one day’s notice.

Your Lordship being out of Town, I submitted the above intentions a few days ago—personally to His Majesty in His Closet—and I added – “that as the arrangements for the next Campaign might possibly come under His Royal Contemplation before my return, I humbly laid myself at His Majesty’s feet for such active employment as he might think me worthy of.”

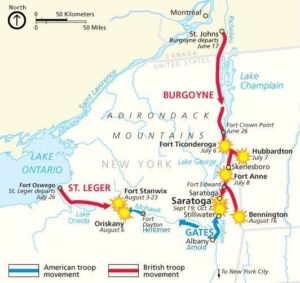

Burgoyne’s plan was not new. It called for a concerted attack to seize possession of the Hudson River-Lake Champlain corridor and isolate New England–the seedbed of the Revolution–from the rest of the continent. The plan called for a three-pronged attack.

- Prong 1: Howe was to sail up the Hudson River to Albany.

- Prong 2: Burgoyne was to sail south on Lake Champlain, to Lake George and the Hudson River to Albany.

- Prong 3: A third army, that eventually fell to the command of Barry St. Leger, was to sail up the St. Lawrence River to Lake Erie and take the Mohawk River to Albany.

The three armies were to converge Albany, where the two generals were to relieve their command to Howe, their superior. Then, if time permitted, they could move eastward into New England and wipe the rebels from the continent. Germaine approved Burgoyne’s plan and gave him command of the primary thrust from Canada.