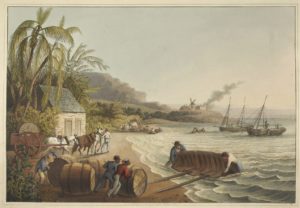

To keep the balance of trade favorable to the mother-country, the British had established laws with its colonies that restricted trade with foreign nations. Among the oldest of the restrictions was the Molasses Act of 1733. The act established a tariff on sugar molasses from non-English colonies, which was vital to supply New England’s thriving rum distilleries. Such restrictions were in vain, as such laws were hardly ever enforced. Smuggling was an American way of life, and the British did little to prevent it. The West India trade helped shape the young nation, but while the colonists prospered the Empire was suffering.

Generations of warfare had depleted the British treasury and the cost of managing a vast colonial empire was growing. The British government financed the Seven Years War by borrowing from British and Dutch bankers, doubling the national debt. After the war, it was believed that renewed warfare with France and their allies was eminent. Officials predicted that ten thousand British soldiers were needed in the colonies for their protection, which would further add to the Crown’s staggering debt. Many people in England were paying higher taxes than in the colonies and believed that the colonists should pay the cost for their protection.

The Sugar Act

One of the principal products produced in New England was rum distilled from sugar molasses imported from the Caribbean. The juice from crushed sugar cane is boiled down to make sugar. The dark syrupy byproduct that remains is sugar molasses and it can be fermented and distilled to make rum. In the French colonies they only made rum from pure sugar cane and considered the molasses a waste product. New England merchants were able to cheaply purchase the molasses from the French to fuel a booming distilling industry in the northeast colonies.

To prevent the loss of revenue to their French competitors, the British placed a tariff on molasses imported from the French colonies as early as 1733. By placing a tariff on imported French molasses the British government hoped that they could dissuade merchants from purchasing molasses from the French colonies or profit off the traffic, but many merchants resorted to smuggling. The tariff was poorly enforced and few followed the law.

To address the rising costs of colonial management, in 1764, the British Government passed the Sugar Act, also known as the American Revenue Act, which replaced the Molasses Act of 1733. Although the Sugar Act called for a lower tariff, the British established a stronger presence in the colonies to ensure it was actually collected. The stricter enforcement made smuggling riskier. The decline in trade, coupled with an increased government presence, provoked the New England colonists to boycott British luxury goods, but it was primarily the merchants and rum distillers in the northeastern colonies that were impacted by the new laws.

The Stamp Act: Taxation without Representation

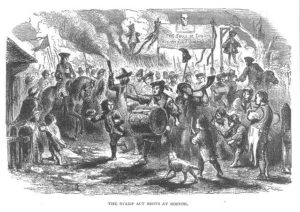

When the Stamp Act was passed the following year, it changed the power dynamic between the colonies and England, causing widespread discord. The tax on newspapers and legal and commercial papers was common in England and the cost was relatively small, but it set a dangerous precedent. The English Bill of Rights (1689) forbid the government from imposing taxes on subjects not represented in Parliament, and the American colonists held no seats in the House of Commons. If these new taxes were allowed to pass without the approval of the colonial legislatures, then the colonists would be denied their rights to representation.

- The Stamp Act was passed in March 1765, but would not go into effect until November, leaving time for the colonists to organize their opposition to the unconstitutional act:

- In July, the Sons of Liberty was founded in Boston and New York City to oppose the unlawful Act, which they did primarily through the use of threats and public demonstrations.

- Benjamin Franklin reprinted his famous “Join or Die” cartoon to unify the colonists. The press was hugely impacted by the Stamp Act and their response was fierce.

In October, the Stamp Act Congress convened in New York City. This was the first gathering of elected representatives from several of the American colonies to devise a unified, but peaceful, protest against the British.

Amid the increased violent protests, British General Thomas Gage, who had become Commander in Chief of British troops in North America in 1763, was forced to withdraw troops from the western frontier to occupy New York City and quell the uprisings. Despite Gage’s presence, protests continued for several months.

As winter approached, the need to provide adequate food and lodging for these troops became critical. In response, the British Parliament passed the Quartering Act that required the local government to quarter troops in public dwellings. This further provoked the colonists. To ease the tension, in April 1766, less than one year after its implementation, the Stamp Act was repealed.

It was in Britain’s interest to preserve peace, but the British Parliament maintained their belief that it was within their rights raise revenue from the colonies. The same day Parliament repealed the Stamp Act, they passed the Declaratory Act that said the Lords could speak on behalf of the colonists in Parliament (virtual representation). By 1767, Parliament passed the Townshend Revenue Act, taxing glass, paper, and tea, which was cause for renewed protests and riots.

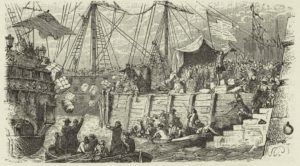

Tea was among the goods taxed under the Townshend Act, and continued boycotts led to huge reserves being built up in Britain’s East India Company’s London storehouses. To prevent the financial collapse of the company, Parliament passed the Tea Act in 1773, which gave the East India Company a monopoly on the trade of tea in the colonies.

In response to the new tax, colonists boycotted tea. Coffee, smuggled from the West Indies, became a popular substitute and coffeehouses a common gathering place. Rather than allowing the tea to spoil in colonial ports, many of the boats were directed back to England. In Massachusetts, however, Governor Thomas Hutchinson had interest in the East India Company and was determined to land his boats. Protesters dressed as Indians boarded one of those ships on December 16, 1773, tossing the tea overboard.

Three of the four acts, known collectively as the Coercive Act in Europe, were directed at Massachusetts in retaliation for the Boston Tea Party. The Acts revoked Massachusetts’s charter, removing its elected members and replacing them with the King’s appointees. They also closed the port until the colonists paid for the destroyed tea and peace was restored. General Gage was ordered to disband local governance in Massachusetts.

The First American Congress

What was most concerning to the colonists was that the Crown could revoke a charter and deny citizens their right to local governance. The colonists dubbed them the “Intolerable Acts.” Aware that Gage was on his way to break up their meeting, the assembly moved their meeting to Concord and organized themselves as the Massachusetts Provincial Congress in October 1774. The seeds of local governance were beginning to form.

At the same time, the First Continental Congress met in Philadelphia. A committee was formed to air their grievances to the Crown. The delegates also resolved to establish a national boycott, that would be enforced by local Committees of Safety organized by the Provincial Congresses. In Massachusetts, the Committee of Safety began coordinating the accumulation of weapons and other military supplies.

In order to secure an arms cache, on April 19, 1775, General Thomas Gage dispatched troops from Boston to an armory in nearby Concord. The troops were intercepted at the Lexington town green by local militia. The militia was outnumbered and fell back, allowing the British to proceed. Fortunes then turned as the British forces were routed in a second confrontation. The British suffered heavy casualties as they were chased back to Boston. The colonists had Gage bottled up in Boston Harbor. All of the colonies raised militias in response to this attack and helped form a siege line that restricted the movement of Gage’s troops.

The American Revolution was now underway.