Andebit et beaqui corendit, ut quostes esciendion re dit ad et prae parion es quia quas alibus sam, omnim faciden ducipidiat arum autem nobis enis es voat

Epilogue: The Aftermath of Burgoyne’s Defeat

The outcome of the Battles of Saratoga had surprisingly wide-reaching effects.

Listen to the Turning Point Trail Epilogue Audio Narration:

After the surrender, Burgoyne, Riedesel, and the rest of the troops became prisoners of war. However, it was a most civilized affair. Rebel General Philip Schuyler invited Burgoyne and the Baron and Baroness Riedesel to his Albany mansion under polite captivity. Schuyler remained in Saratoga so he could begin construction of his new home—which ironically Burgoyne had destroyed—sending his aid ahead to Albany to prepare for their guests. After he set construction in motion, Schuyler joined his guests in his Albany home. There Burgoyne was lodged in the best apartment in the house. An excellent supper was served him in the evening, the honors of which were done with so much grace, that he was deeply affected.

Burgoyne asked General Schuyler, “Is it to me, who have done you so much injury, that you show so much kindness!”

“That is the fate of war,” replied Schuyler, “let us say no more about it.”

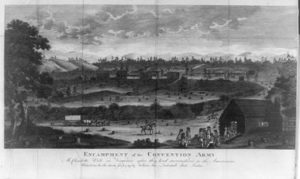

Burgoyne’s soldiers camped on the hill behind Schuyler’s mansion, causing trouble in their restlessness. The Germans were stealing potatoes and others were building shelters using Schuyler’s fencing. Playing host to 4,000 soldiers tried the patience of Mrs. Schuyler, but Burgoyne and his men were soon sent to Boston as agreed upon in the convention.

Burgoyne’s defeated army made the long march from Albany to Cambridge, near Boston, to embark for Europe. George Washington, however, was not convinced that Burgoyne and his troops intended to honor their agreement not to serve again in arms against the Americans. Congress agreed that they could go once the British government approved the terms of the capitulation, but the British did not recognize the authority of Congress as a lawful body and so the troops were kept in “captive limbo” in America. Finding an adequate food supply for the captive troops in New England proved to be a challenge. On October 15, 1778, Congress decided to march all 5,900 troops under the command of Major General Phillips 700 miles south to Charlottesville, Virginia.

Burgoyne was allowed to return to England to seek formal ratification of the Convention of Saratoga. He arrived in early 1778. He defended himself in the House of Commons on May 26, 1778. Burgoyne blamed Lord George Germaine, Secretary of State for America, for mishandling the orders, and Germaine in turn blamed General William Howe, Commander-in-Chief of the British Troops in North America, for not assisting Burgoyne. After testifying, Burgoyne retired to the city of Bath in England. When his political friends came into office, Burgoyne’s rank was restored, but he never saw active service again.

Burgoyne settled into civilized life, where it is reported he enjoyed gambling and became a playwright and theatre aficionado. His most notable works were The Maid of Oaks and The Heiress.

Global Consequences

Burgoyne may have retreated from military life, but the effects of the Rebel victory in Saratoga spread far and wide. During this time, Benjamin Franklin was serving as the American ambassador to France (1776 to 1783). The French had secretly been supplying the Rebels with guns and munitions since 1775, but Franklin was sent to convince France’s King Louis XVI to play a more active role in the war. France was still sore from their defeat in the French and Indian War (Seven Years War), but after the American victory in Saratoga, they pledged their full support.

In fact, France was the first European country to formally recognize the United States on February 6, 1778, with the signing of the Treaty of Alliance. From then on, they openly supplied the Rebels and provided a combat army to serve under George Washington. In the later years of the Revolutionary War, France also sent a naval force that was significant. Their participation turned the tide of the war, leading historians to dub Saratoga “the turning point of the American Revolution.”

In all, the French spent about 1.3 billion livres (in modern currency, approximately 13 billion U.S. dollars) supporting the Rebel cause against the British. This expense, combined with the exorbitant lifestyle of the French Monarch Louis XVI, bankrupted the nation. Taxes were levied against France’s citizens, but exemptions were offered to noblemen and clergymen, putting an onerous burden on the lower class. The burden of taxes combined with years of poor harvests left many Frenchmen poor and starving, with little help or sympathy from their King. These were significant contributing factors that ignited the French Revolution.

The French Revolution began in 1789 and ended in the late 1790s, with the ascent of Napoleon Bonaparte. Napoleon conquered most of the European continent before being defeated by a coalition of nations in 1815.

The rise and fall of Napoleon had a lasting impact. The numerous small nation-states that made up much of central Europe recognized that they could not defend themselves against more powerful foes. Consolidation of power was needed to restore balance to Europe. This led to the unification of the numerous states within Germany and Italy.

The powers of these newly unified European nations continued to grow—fueled by the Industrial Revolution and the conquering of new lands (Imperialism). An arms race ensued as each nation worked to tip the balance of power in their favor. As the imperial powers became more dominant, countries formed defensive alliances. Britain and France put aside centuries of conflict and joined Russia and others in an alliance known as the Allied Powers against Germany, Austria-Hungry, Italy, and others who were in an alliance known as the Central Powers. When Austria’s Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated in 1914, it activated these alliances and sent the world to war.

The Treaty of Versailles that ended World War I forced the Germans to take moral responsibility and pay reparation to the Allied Powers. This, combined with the devastating effects of the Great Depression, sent Germany into an economic tailspin. Desperate, Germans put their hopes in a charismatic leader who promised to put an end to their misery and restore Germany to its former glory—Adolph Hitler

When Hitler took power, he resented the restrictions put on Germany by the Treaty of Versailles. He began to rearm Germany. Hitler succeeded in conquering most of Europe until he made the same mistake that ended Napoleon’s rise to power: He attempted to invade Russia. At the end of World War II, the victorious Allies redrew borders. They split Europe into eastern and western blocks, divided Austria-Hungry, and redrew the boundaries of the Middle East to give Jewish people a homeland. This launched the democratic western nations against the communist East, kicking off the Cold War. In addition, armed conflicts in the Middle East increased as cultures clashed under the new nation-states and borders created by outsiders.

Thus, one could say that the events that transpired in the wilderness of the New World in summer and fall of 1777 triggered a chain of events that changed the course of world history. The New York Times called it the most important battle in 1,000 years. It was the turning point of the Revolutionary War that gave rise to the United States and resulted in the world powers and global struggles we know today.