Andebit et beaqui corendit, ut quostes esciendion re dit ad et prae parion es quia quas alibus sam, omnim faciden ducipidiat arum autem nobis enis es voat

6. Penfield Homestead Museum

Railroads Kick Start the Age of Iron

Listen to the Site 6 Iron Story Audio Narration

It was two adventurous boys that led to the discovery of the most important ore beds in Crown Point: A boy hunting for bees on his father’s property in 1821 uncovered what would become the Hammond Ore Bed. Just five years later, another boy, named R. L. Cram, was hunting for partridge only a short distance from the Hammond Bed. As he grasped a bush to pull himself up a steep mountainside the whole mass detached from the rock, revealing shining ore beneath. He took samples of it to his father, who owned the land. His father opened the bed, realized the value, and soon sold it to Allen Penfield and Timothy Taft (who sold his interest several years later). This bed was known as the Penfield Iron Ore Bed. The bed had six different openings, the bed varying in thickness from five to 30 feet. The ore was black, containing no sulfur, and only a slight trace of phosphorus. In other words, it was quite pure and valuable. Allen Penfield, Taft, and later Charles Hammond, worked the Penfield Bed. The ore had been tested and deemed superior. Beginning in 1828, the Penfield ore was transported 4.5 miles east to a cold-blast Catalan forge at Ironville. The original forge had two water wheels and employed about 40 men. Over the years, the forges were improved and expanded. In 1873, the Ironville forge became the property of the Crown Point Iron Company. The Penfield Bed was worked until the late 1880s when no more ore could be mined from it. From the earliest days, the Penfield’s developed various ways to improve efficiency. Most notable, was, in 1831, the use of an electromagnet to separate the iron from the crushed ore. It’s for this reason that Ironville is considered the birthplace of the “Electric Age,” as it was where the first industrial application of electricity took place in the United States. The electromagnet came from Professor Joseph Henry of the Albany Academy in Albany, who later became famous for his experiments with electricity and a director of the Smithsonian Institution. As Ironville was expanding its operation, demand for high-quality iron was growing nationally. The once-vital lumber industry in this area was becoming overshadowed by a more “modern” resource: iron. That’s because, in the 1830s, the age of the railroad was beginning to blossom across the country. The first railroad in New York, linking Albany and Schenectady, was opened to the public in 1831—though the first rail lines would not reach the Port Henry-Crown Point region until 1869-71. By 1860, the Midwest had constructed lines that linked every major city. To make rails, of course, you needed iron (and later steel). It is perhaps for this reason that Charles Hammond had held off doing anything with the Hammond Ore Bed when it was first discovered in the 1820s. At that time, he was probably still focused on his successful lumber business. In fact, he owned mills and forestland all over the Adirondacks. It wasn’t until the early 1840s that Hammond acted on doing something with his iron bed. Charles’s brother, John, was initially unsure, but Hammond decided to have the ore tested by the Peru Iron Company in Clintonville. He wrote:

“The foremen and his workmen at Clintonville said when rolling it that they never saw iron that would roll into thin 4d plate for 4d nails without cracks or fractures on the edge before this; that their Peru iron was the best, but it would not stand the test for strength and toughness by the side of mine.… [I] finally came into the arrangement to build a blast furnace in 1845, after I had found and engaged a man to join us that had experience in building and running furnaces.”

The man Hammond engaged was Jonas Tower. In 1845, Charles Hammond founded the Crown Point Iron Company, along with his brother John C. Hammond, his brother-in-law Allen Penfield, and Tower. The company’s 45-foot-tall blast furnace was blown in on January 1, 1846, and worked primarily Hammond Bed ore—some of the highest quality ore in the country. The Hammond furnace was unique: Although it was a blast furnace, the escaped heat was used not only for making steam to run the blast power, but also for stamping ore, for sawing coal brands, and for grinding feed. This furnace churned out 3,500 tons of pig iron a year, until the Hammond Bed was exhausted around 1870. It was ore from this bed that was rolled into plates for the ironclad ship USS Monitor. (See Learn More.) Some of this iron was also used for the suspension cables of the Brooklyn Bridge. In fact, a plank bridge that ran across the current pond behind the forge, connecting the workers’ hamlet on the other side of Putt’s Creek, was dubbed the “Bridge to Brooklyn.” Charcoal wagons also used this bridge, bringing charcoal from the woods to fuel the furnace.

The current site of the museum was the private residence of the Penfield family. And while the surrounding area now looks like peaceful farmland, it would have been a lively town in its day, with forges and two cupola furnaces, a school, and a variety of stores.

Steel’s Advantage

The reason that the Hammond and Penfield iron—and most other Crown Point-Moriah iron—was so coveted was that it had such low levels of impurities, particularly phosphorus. This made it ideal for transforming into steel—a superior product to iron. The difference between iron and steel is that iron is an element, and steel is an alloy of iron, small amounts of carbon, and another material, usually chromium. By alloying—or combining–iron with other elements, it becomes stronger.

Transforming iron into steel was not easy. But a new method promised to change that: The Bessemer process. In 1863, Alexander Holley returned from England having purchased the U.S. patent rights to the Bessemer machinery. Partner in a Troy-based company at the time, Holley is often dubbed the father of the American steel industry for bringing the Bessemer technology to the U.S. Two years later, the much-prized, low-phosphorus pig iron produced from the Hammond Bed was some of the first used in this experimental production of steel at one of the first Bessemer plants in the United States. The plant was on the Wynants Kill, an industrial river in Troy.

It’s worth noting that these events were not happening in isolation. At the same time near Moriah, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute alum and Port Henry native Thomas Witherbee was experimenting in his lab in Fletcherville–taking a scientific approach for creating proper mixes of ore to be sent to Holley and his colleagues.

Travel Tools

Right before the Penfield Museum, on the left side of the road, is a sign for Peasley Road. Turn left on Peasley Road and go about 100 yards to a parking area on your right, just before the bridge. Walk across the bridge and immediately walk up the embankment onto the trail. You’ll see a CATS trail sign, marking the beginning of the Penfield Pond Trail. This 1-mile loop trail goes above a cascading brook, arrives at the peaceful waters of Penfield Pond, and then passes through the old forest along the shore.

The Penfield Homestead Museum has assembled an impressive archive of historic photographs and drawings to help visualize the complex. The museum also houses a replica of the large electromagnet, which is now in the Smithsonian Institute in Washington, D.C. Visit the museum, follow the walking tour and CATS trail to get the whole picture. The industrial structures that supported the booming iron business are long gone, but a few buildings survive. Although the millpond has nearly filled with vegetation, it once provided sufficient water to drive the forges, crushers and separating mill as well as the grist and sawmills below the dam.

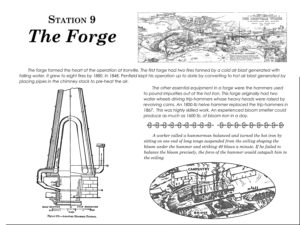

The forge currently at the museum is not original. It is a Catalan, cold-blast bloomery forge built in 1976 that came from Frontier Town, a former amusement park in North Hudson. It is based on a design built by Major Philip Skene in the 1700s in Whitehall. Skene’s forge was a primitive, cold-blast bloomery forge, which had the notable distinction of producing the wrought iron that went into the ships build by Benedict Arnold during the Revolutionary War. While it is a good example of a primitive bloomery forge, it does not represent any of the forges that were used in Ironville.![]()

Detour: Peasley Road Bridge and Stoddard’s Rock

First Person Account:

Charles Hammond was well respected in his time: “Charles F. Hammond was the leading spirit in discovering and developing the iron interest of this town. He foresaw, apparently from the outset, its importance and the possibilities of turning it to profitable account.” -Thomas Witherbee

Charles Hammond trying to decide to work the Hammond ore bed: “I had analyses made of the ore and had it worked in a forge and the iron rolled into round and band iron, and also into nails and tested by the Peru Iron Company at Clintonville. Some of the bar iron I had made at Penfield’s and some at Vergennes, Vt., where there were forges at the time. The foreman and his workmen at Clintonville said when rolling it that they never saw iron that would roll into thin plate for nails without cracks or fractures on the edge, before this; that their Peru iron was called the best, but it would not stand the test for strength and toughness by the side of mine. I then got out about twenty tons of the ore at great expense and trouble for the want of a road, being obliged to use oxen on a wood-shod sled to haul it to the Wooster place on bare ground, and from there I drew it to the wharf on a wagon. I shipped it to Greenbush and took it from there by rail to Stockbridge, Mass. It was there worked in a small charcoal furnace, yielding a very fine quality of pig iron.”