Andebit et beaqui corendit, ut quostes esciendion re dit ad et prae parion es quia quas alibus sam, omnim faciden ducipidiat arum autem nobis enis es voat

7. Driving to Hammondville

The Boom Years of Iron

Listen to the Site 7 Iron Story Narration

One year after the new Crown Point Iron Company was formed in 1845, the company town Hammondville was established. The village of Hammondville was one of many short-lived mining towns. It was built, owned, and operated by the Crown Point Iron Company to facilitate their iron-ore mining enterprise and abandoned during the 1890s when that venture failed. The majority of Hammondville residents were recent immigrants from Ireland, Quebec, Sweden, and England, although native-born Americans also lived and worked at the site. During the course of the occupation, the population ranged from 400 to as many as 1,000 people. Mining at Hammondville carried on day and night. In 1874, the mines were yielding 125 tons of ore a day to be shipped to Troy. Hammondville was truly a “company town.” The company provided most of the amenities of daily life, owned all land, buildings, and transportation routes, required employees to live in company housing, and prohibited alcohol, swearing, and the mistreatment of horses on its property. To house the workforce, the company built single-family homes for management, multi-family tenements and double houses for workers with families, boarding houses for single men, a church, a school, a doctor’s office, and a company store. The village was comprised of two main parts: The village proper, where the mines, industrial structures, and residences of the newly hired were; and the Old Furnace District, the site of the original settlement and home to long-time employees. But the most obvious symbol of company control was the superintendent’s house, located in the center of the village and raised above the main road on a terraced lawn. This was also the site of the village well. Although Hammondville was a company town with labor under close surveillance and controlled by the bosses, a vibrant community identity developed. The villagers were members of the Hammondville Golden Coronet Band or the Hammondville Bessemers baseball team. While the Hammondville band provided community-sponsored music for events and celebrations, music was also an important part of less formal social occasions, as well as life at home. Several villagers were known for their skills playing the fiddle or violin. For instance, Moses Ploof, who formed one half of the “famous stringed duet that used to play for the dances and other festivities that made the gatherings in the famed mining camp a great event,” was also locally renowned as a violin-maker. Melvin Turner, the village doctor, also played violin, although apparently without Ploof’s skill. In a 1911 letter reminiscing about music at Hammondville, E.G. Locke wrote, “When Doc was not busy dealing out pills, liniments and other concoctions that were warranted to kill or cure, he was busy rasping away on the violin and the squeaks and groans that came from the violin would rival those from Doc’s patients when he was extracting their teeth.”

The population of Hammondville grew to 1,000. Yet that would soon change. By the late 1860s, the Crown Point Iron Company recognized that it needed to modernize and move its furnaces to the lakeshore, where they could be powered by anthracite coal coming from Pennsylvania by train. The seemingly inexhaustible supply of wood with which to make charcoal was becoming more and more scarce. After 1861, wood for fuel became so scarce that the Hammond furnace could only be run about three-fourths of the time. After the Hammondville furnace closed in 1872, an 1875 Plattsburgh “Republican” newspaper writer visited the site and called the giant pile of blast furnace slag located near the remains of the furnace evidence of the enormous amount of iron formerly made here: “…we gaze about on one of the roughest, ruggedest, rockiest scenes… Huge bare rocks arise to the left, while in front, belonging to the same range, is Knob Mountain, a bare, round rock, having a perpendicular precipice upon the western side, from five to eight hundred feet high.”With the depletion of wood for charcoal, anthracite coal became the preferred fuel. During this same time, railroads were constructed along the west side of Lake Champlain. Trains brought anthracite coal from Pennsylvania mines north to Albany and beyond. This necessary resource could now be brought economically up to Crown Point. Larger, modern blast furnaces burning coal along the lake were now feasible. Residents saw the move with great optimism. In the pages of Essex County Republican, a writer with the pseudonym Nemo believed “it will be seen that all classes share in the benefit of this great enterprise, while our mineral wealth is destined to yield ample return for this lavish outlay of capital.”This attitude was a reflection of the country’s positive attitude after the Civil War: After the war, industrial growth exploded. Elmer Eugene Barker, a Hammond relative, wrote in 1942 in The Story of Crown Point that “A pioneer attitude and method of attacking nature’s resources had changed to an advanced standard of exploitation; local industries had become transformed into big industries or had given way to more concentrated establishments elsewhere. Primitive methods of production and manufacture had become outmoded and old plants had become inadequate to supply increased demands.”The Hammonds, however, needed more capital to restructure the business and build furnaces on the lake. The second Crown Point Iron Company, incorporated in 1872, brought in high profile investors—many of whom were “outsiders” from the Troy-Albany area. Some had other business interests that could be considered in competition with the Crown Point Iron Company—such as Pennsylvania iron companies, and more locally, the Chateauguay Iron and Ore Company. To stay competitive and to maximize profits, the “new” Crown Point Iron Company made two big investments. The first was the construction of two Bessemer furnaces at Hammond’s Wharf on Lake Champlain (site of present-day Monitor Bay).

Troy industrialists were aware of the high-quality iron in Crown Point for use in the Bessemer steelmaking process. Alexander Holley had been hired by John Flack Winslow, manager of Albany Iron Works, and John A. Griswold of Rensselaer Iron Work to purchase the patent to the Bessemer machinery in England in 1863. In 1864 they began construction of the Bessemer Steel Works in Troy. Holley stayed current with the evolving technologies related to the Bessemer process, advising iron industries in Troy and Pennsylvania. He drew detailed diagrams for Crown Point’s Bessemer furnace, writing about it for a London journal, Engineering, in 1878. The two steel-jacketed furnaces were both built in 1873, one 60’ tall and the other 70’ tall. The furnaces produced 45,000 net tons of Bessemer pig iron a year. The second investment was provided by the benefit of Crown Point’s relationship with the Delaware & Hudson Canal Company. The D&H President, Thomas Dickson, was also a shareholder in the reincorporated Crown Point Iron Company. In 1872, Thomas Dickson put a Delaware & Hudson engineer to work, plotting a course for a 13-mile-long narrow gauge railroad that would speed the transport of iron ore in the mountains to the furnaces at the wharf. In addition to transporting the iron, the new Crown Point Iron Company Railroad had a passenger car and a mail car. Thus the new railroad became the main form of east-west transportation, connecting Hammondville and Ironville with the two lakeside Bessemer furnaces—it even transported two pianos to Hammondville.

The spring of 1874 marked a brief decline in the iron market and the company experienced its first major labor dispute. The event became known as the “Swede strike.” (See Learn More: The Panics and Swedish Labor Strife.) The strike was quickly dealt with, and although it resulted in the arrest of several men and the termination of several others, work at the mines quickly resumed. Delaware & Hudson Canal Company’s intention to connect Crown Point Iron Company’s mines to the facilities at the lake was integral to a much larger plan. The Delaware & Hudson Company was in the process of connecting several rail lines to complete the north-south railroad line along the western shores of Lake Champlain. In 1873, the D&H had arranged for the creation of the New York and Canada Railroad, a merger of the Whitehall and Plattsburgh Railroad and the Montreal and Plattsburg Railroad (owned by the Rutland Railroad). This combined railroad would extend rail lines from Whitehall to Quebec. By 1875, the line was completed, allowing iron to be shipped south by rail as well as by boats on the Champlain Canal. Increasingly important anthracite coal from Pennsylvania was becoming the fuel of choice as the Adirondack forest was stripped bare through the charcoal-making process. The coal and other supplies and machinery could be shipped north year-round by rail while transport by the canal boats was seasonal. The iron business was booming. In 1875, the Albany and Rensselaer Iron and Steel Company was using upwards of 8,000 tons of ore a month, with Crown Point being one of its main suppliers. After Charles Hammond died in 1873—only three weeks after the tragic death of his son Thomas—the surviving son, John Hammond, was the only Hammond left in the family business. (Charles’s brother, John, died of pneumonia in 1858.) The deaths of Thomas and Charles Hammond not only left General John Hammond as the sole local stockholder in the Crown Point Iron Company, but it also left him without allies in the company and without the trusted counsel of his father and brother. These losses later factored into events that damaged John Hammond’s interests as well as the company as a whole. However, this would not become apparent for several years. After the demise of the Crown Point Iron Company, the American Steel and Wire Co. purchased the company and all of its holdings in 1897. Most remaining Hammondville residents soon abandoned the town and in March 1900, American Steel and Wire began auctioning off architectural materials and equipment from the village. Hammondville was literally disassembled and sold off piece-by-piece, leaving only foundations and cellar holes at the site.

Travel Tools

Driving west along Furnace Road to Hammondville, you can imagine the Crown Point Iron Company Railroad that would have been running along your left side. The narrow-gauge train climbed 1,300 feet from the shore of Lake Champlain to Hammondville, running alongside Furnace Road and crossing it twice before reaching Hogback Road. There, it passed through a deep rock cut where engines could take on water before climbing up to mines and ore-processing mills that are now entirely over-run with second-growth forest. If you look carefully, you can still see the remains of the old railroad bed in certain spots. The most visible is just past the intersection with Corduroy Road, angling off to the left. Stone walls crisscrossing the open fields here show the extent of farming in the area. It’s an example of industry and farming side-by-side: After all, the miners needed to be fed.

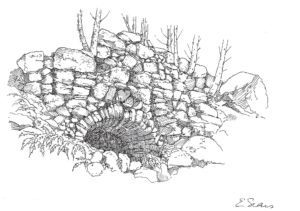

At the intersection with Hogback Road, turn left. About ten miles, on your right-hand side, you’ll see a small pull-off, where waste slag from the Hammondville furnace is visible. The furnace, which is now moss-covered and hidden in the trees across the road on private land, ran from 1846 to 1870. Waste slag from nearly 30 years of continuous production has filled the small ravine adjacent to the pull-off where town highway crews load up with it when they need fill. Look for intensely blue and green glassy globs.![]()

First Person Account:

Slag–the remains of the iron-smelting process–can be quite beautiful and can still be found in woods of what was once Hammondville: “Winslow Watson visited this [Hammondville] furnace in 1852 and has left the following account of what he saw there: ‘In approaching the furnace I observed the road for some distance was formed by a very beautiful material, exhibiting a surface soft and lustrous and glowing in every shade and tint. this substance was the concretion of slag or cinders of the furnace. When gushing from the stack in fusion, it will form and draw out, by a wire trust into the boiling mass, an attenuated glass thread the entire length of the furnace, a distance of 60 feet. The glass presents a most delicate and- diversified coloring although combined in the eruption from the furnace with extraneous properties. Thus beautiful in its crude and adulterated condition may not this substance, purified and refined by science be rendered subservient to the arts?’ At the present day, in the forest growth that has since overrun the site of this historic enterprise, pieces of this glassy slag are to be found, their varying tones of blue and green as fresh as when Watson saw them nearly ninety years ago. The roads for some distance away, now winding through shady woods, have been repaired with this rare material which so excited his admiration and imagination at that time.” -From E.E. Barker, The Story of Crown Point Iron, 1942.