Andebit et beaqui corendit, ut quostes esciendion re dit ad et prae parion es quia quas alibus sam, omnim faciden ducipidiat arum autem nobis enis es voat

28. Hammond Wharf at Monitor Bay Park

The End of an Era

Audio Narration for Site 28 of the Iron Story

After reincorporating in 1872, Crown Point Iron Company built its 13-mile-long narrow gauge railroad from Hammondville to the lakeshore. It was here, in 1872, that the company’s “double blast furnace of mammoth proportions” was built, looming “skyward near Hammond wharf, erected at a cost of nearly half a million dollars, and said to be one of the most perfect models of modern times,” according to a local newspaper article. (That same year, Penfield sold all his interest in the company to Hammond.) The two steel furnaces at the wharf required anthracite and coke, as opposed to the earlier Adirondack iron fuel of charcoal, and were capable of producing 45,000 tons of Bessemer pig iron a year.

For a decade business was good. But in 1883, depression struck the steel industry, and the Crown Point Iron Company recorded its first loss. It was not feasible to shut down entirely, so the products of the mine accumulated, as the market would not absorb even a reduced output. Elmer Eugene Barker, a Hammond relative, wrote in The Story of Crown Point in 1942: “Ore lay in great heaps at the mouths of the mines, about the furnaces, and at the wharf. By the first of January 1884, this surplus amounted to more than 32,000 tons of furnace ore.”

Barker’s attitude was similar to that of other locals: As the influence of out-of-town investors “became more potent in determining business policy, its management became less efficient and economical. Because of interlocking interests of certain members of the Crown Point Iron Company with the Chateauguay Ore and Iron Company, favors were made to the latter company, which, unfortunately, proved to be detrimental to the interests of the Crown Point business.” There’s certainly some truth to Barker’s sentiments—it would explain why the iron industry in Port Henry managed to last for another 80 years. Yet the iron and steel industry was changing regionally and nationally.

The 1883 depression in the steel industry began a decade of decline for the Crown Point Iron Company. Machinery was in regular need of costly repairs, the ore beds at Hammondville began to show signs of exhaustion, and workers were gradually leaving to find work at the enormous iron mines in Wisconsin and Minnesota, particularly at the Mesabi Iron Range in Minnesota. These Midwest ore beds were more advantageously located and more economical for mining and shipping. That’s because—unlike the large deep, vertical veins of Adirondack iron—the Midwest iron deposits were shallow and horizontal, allowing for enormous open-pit mines that were easier to access and to mine.

In 1889, John Hammond owner and president of the Crown Point Iron Company died and control of the company passed from local to non-local residents. The final shipments of Crown Point ore were mined in 1893 and soon after, American Steel & Wire Company purchased the property for far less than what it had once been worth. Furnaces and buildings were dismantled and repurposed and railroad tracks were torn up and sold for scrap. American Steel & Wire made an effort to heal the landscape from the scars that mining had produced. A 1922 Ticonderoga Sentinel article reported that the new owners of the property had planted 262,500 trees and enacted fish and wildlife management practices and fire prevention programs at the site of the former company town.

Travel Tools

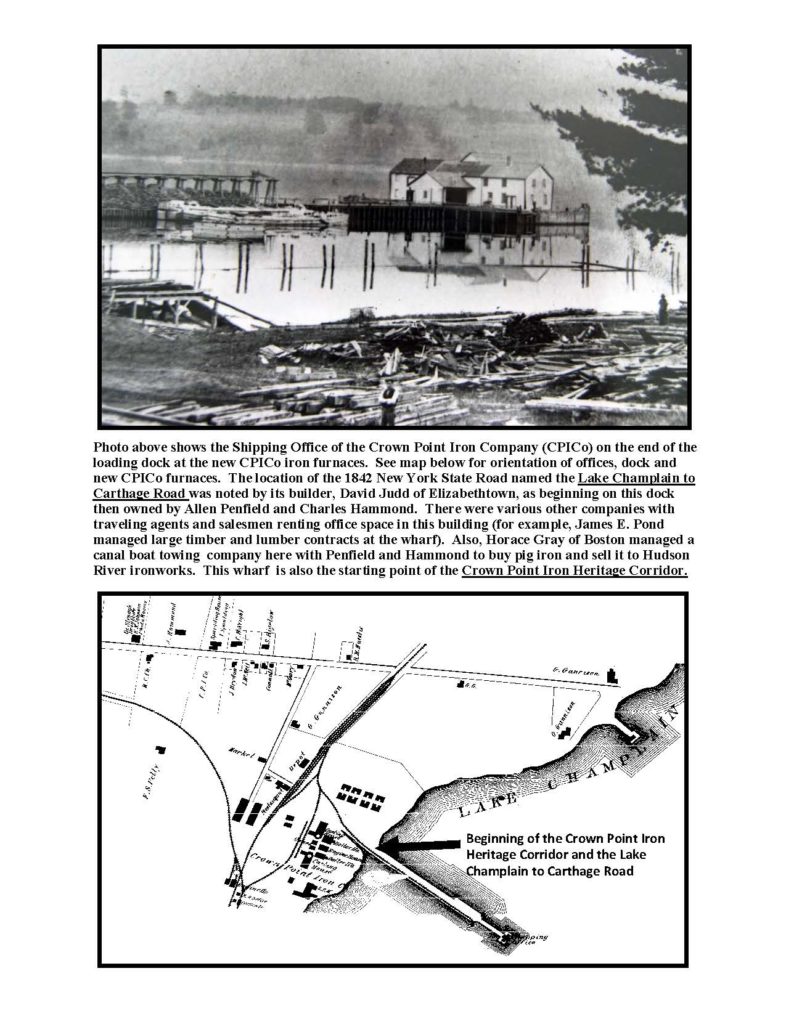

Monitor Bay Park, now the Crown Point municipal campground, occupies a portion of the site of Crown Point Iron Company blast furnaces, built to process iron ore mined in Hammondville, then transported to the lakeshore on the Crown Point Iron Company Railroad. The narrow-gauge (3’) tracks ended at the furnace complex, which consisted of two ovens, two boiler houses, two casting houses and coal bunkers, located on the north (park) side of the pier.

The pier, now used for fishing, served as a loading dock, with a shipping office at the end and a canal on its south side. The canal reached more than 200 yards inland and was wide enough for canal boats to come in and load up. Tracks of the Delaware and Hudson (standard gauge) railroad ran along the pier, almost out to the shipping office. The two railroads did not connect directly, but sidings of both lines ran up alongside the furnace complex.

The shoreline here is made up mostly of slag, waste material from nearly 20 years of pig iron production. This is not the pretty blue, glassy slag from Hammondville or Penfield, but craggy chunks of clinker blackened by the fires of blast furnaces. To the south of the pier, a shoreline of broken rock and debris, now covered with trees and shrubs, rises steeply for 20 to 30 feet, leveled off at the top. This rubble is from the demolition of the Crown Point Iron Company complex, which stretches for several hundred yards, is visible from the water when leaves are off the trees.

Now, only one industry remains on the lake. Looking south, you can see the International Paper Mill in Ticonderoga.

Learn More

First-Person Account

A bittersweet epilogue to the life of the Crown Point Iron Company: “In 1900, I was opening up some new mine for the American Steel & Wire Company at Hibbing, Minnesota, and when I got on the ground, I found four carloads of boilers and mining machinery from Hammondville. It seemed like meeting an old friend. I was told later that it was the last shipment over the Crown Point Railroad before the rails were taken up. I saw this machinery installed at Hammondville in 1873 and used it again in the development of the Clark mine in 1900.” -A letter from former mine superintendent William C. Northey, September 1940