Andebit et beaqui corendit, ut quostes esciendion re dit ad et prae parion es quia quas alibus sam, omnim faciden ducipidiat arum autem nobis enis es voat

19. Driving Joyce Road to the Plank Road

Roads and Railways

Listen to the Iron Story Site 19 Audio Narration

The development of transportation was also influenced by the iron industry. Several so-called plank roads were built and maintained largely by iron entrepreneurs. Geographer John Moravek writes that “in some whole towns, such as Moriah, Black Brook, Dannemora, Ausable, and Aranac, virtually every road interconnected mining, charcoaling, and iron-making settlements. Many roads in these other areas were privately financed by iron concerns.”

In the late 1840s, the Moriah Plank Road was laid to ease the passage of cartloads of hundreds of tons of iron ore on the way to Port Henry furnaces and docks. Plank roads like this one were made from pine or hemlock planks cut to three- or four-inch thickness. A bed of planks called stringers or sleepers was laid horizontally in the roadbed for the vertical planks of the road surface to rest on, flush to the ground at each edge. However, especially in Moriah because of the constant weight of the wagonloads carrying five to seven tons of ore, plank roads were found to last only four or five years before needing replacement instead of the estimated eight to twelve when plank roads were first proposed.

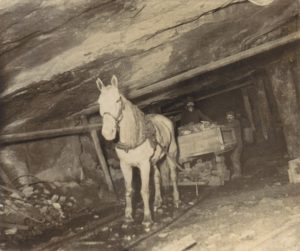

The mining companies contracted with teamsters who owned the horses. Maintenance of the plank roads was costly and area sawmills were kept busy furnishing plank material. When the wagons were unloaded in Port Henry, the ore was washed from the wagons before the return trip up the steep grade to the mines. In its peak period of operation, as many as 100 teams hauled ore daily over the Moriah Plank Road. (Decades later, when sports competition between communities was high, one Port Henry baseball team was called the “Wagon Washers;” a Mineville team was the “Iron Ore Eaters.”)The Civil War’s monstrous appetite for iron—for horseshoes, artillery, cannonballs, rifles, armor plates—exposed the greatest obstacle to iron production in Moriah: getting ore from the mines to the lakeshore. Even 100 teams of horses hauling wagons down the Plank Road could not keep up with the demand from iron furnaces in Troy, Pennsylvania, and Ohio.

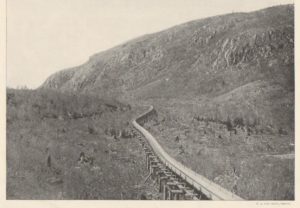

Around the time of the Civil War, as soon as capital could be raised, work began on railroads. In the building of the region’s rail lines, the iron industry played a major role. The Delaware and Hudson Canal Company eventually built the region’s north-south rail line. The four branch lines built inland during this period were constructed almost solely by and for the iron interests.Witherbee, Sherman and Company built and maintained the Lake Champlain & Moriah Railroad. After 20 years of using the Moriah Plank Road, the Lake Champlain & Moriah Railroad became the industrial thoroughfare from Mineville to Port Henry. The train route climbed 1,309 feet in elevation over 7.5 miles, one of the steepest grades in the country. Three switchbacks, known as Ys, were required to clear the incline. The rail line dropped the cost of transporting ore from 90 cents per ton to 32 cents and fueled a production boom. Later a passenger station opened in 1872 that traveled between Port Henry and Mineville. The trip took almost an hour.

In some areas, after the decline of the iron industry, roads built by iron companies that were well-placed to serve other users became toll-free public roads.

Travel Tools

Don’t miss the enormous tailings pile on the north (left) side of Joyce Road. The tailings are still used today by the Moriah town highway department to sand or improve the roads. You’ll also see more concrete company homes on Joyce Road.