Andebit et beaqui corendit, ut quostes esciendion re dit ad et prae parion es quia quas alibus sam, omnim faciden ducipidiat arum autem nobis enis es voat

23. Powerhouse Park

Shorelines as Sites of Industry

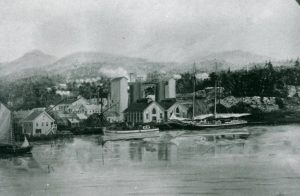

The first sail ferry service was established here in 1785, eight years before the first road was built. The ferry ran from here to Crown Point. In the early 1800s, steamboats running from Whitehall to Burlington would stop at Port Henry. Later the G.R. Sherman ferry began carrying passengers, operating until 1929 when the Crown Point bridge was completed. After the Champlain Canal opened in 1823, Major James Dalliba and John Dickerson of Troy were among the first to send a shipment of iron out of Essex County to markets south. Dalliba had served at the West Troy (Watervliet) Arsenal following the War of 1812, where he became familiar with the quality of Cheever iron ore. He and Dickerson purchased 4,000 acres of land, including the Cheever ore bed and built a furnace to refine the ore, pig iron being easier to transport than lumps of ore. When Dalliba and his wife made permanent residence in the area, then known as Lewis Mills, he changed the name to what it still is today: Port Henry, in honor of his friendship with his wife’s uncle, Henry Huntington. (Port Henry was incorporated as a village within the town of Moriah in 1869, and in 2017 the village was dissolved.)

The first sail ferry service was established here in 1785, eight years before the first road was built. The ferry ran from here to Crown Point. In the early 1800s, steamboats running from Whitehall to Burlington would stop at Port Henry. Later the G.R. Sherman ferry began carrying passengers, operating until 1929 when the Crown Point bridge was completed. After the Champlain Canal opened in 1823, Major James Dalliba and John Dickerson of Troy were among the first to send a shipment of iron out of Essex County to markets south. Dalliba had served at the West Troy (Watervliet) Arsenal following the War of 1812, where he became familiar with the quality of Cheever iron ore. He and Dickerson purchased 4,000 acres of land, including the Cheever ore bed and built a furnace to refine the ore, pig iron being easier to transport than lumps of ore. When Dalliba and his wife made permanent residence in the area, then known as Lewis Mills, he changed the name to what it still is today: Port Henry, in honor of his friendship with his wife’s uncle, Henry Huntington. (Port Henry was incorporated as a village within the town of Moriah in 1869, and in 2017 the village was dissolved.) After Dalliba died in 1832, the turnover of this property became frequent. One of the longest, most successful owners was the Bay State Iron Company, which ran the furnaces between 1867 and 1883. Then, in 1883, it became the property of Witherbee, Sherman, but the operation of this two-furnace facility was uneconomical. Following the Panic of 1893, they fell idle and the furnaces were dismantled in 1896.Other industries took iron’s place: A power plant, whose 165-foot stack once punctuated Port Henry’s skyline, stood here. Power could be generated cheaply here with coal deliveries by barge. The power plant operated from 1907-1923. In 1973, 100 pounds of dynamite toppled the smokestack and a wrecking ball leveled its 40-inch-thick concrete walls.

After Dalliba died in 1832, the turnover of this property became frequent. One of the longest, most successful owners was the Bay State Iron Company, which ran the furnaces between 1867 and 1883. Then, in 1883, it became the property of Witherbee, Sherman, but the operation of this two-furnace facility was uneconomical. Following the Panic of 1893, they fell idle and the furnaces were dismantled in 1896.Other industries took iron’s place: A power plant, whose 165-foot stack once punctuated Port Henry’s skyline, stood here. Power could be generated cheaply here with coal deliveries by barge. The power plant operated from 1907-1923. In 1973, 100 pounds of dynamite toppled the smokestack and a wrecking ball leveled its 40-inch-thick concrete walls.

Today we think differently of our waterfronts. We tend to use them as recreational sites—not factory sites.

Travel Tools

As you drive down the hill, south on Route 22, before you turn left to Powerhouse Park, you’ll see the remains of an elaborate stone wall on your right and the ruins of a white wooden house. The was the site of Dalliba’s home. The building you see in front was likely the servant’s quarters. The original home sat further back and was destroyed in a fire.

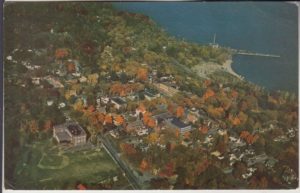

Turn left at the sign for Powerhouse Park (Dock St.). Cross over the tracks and continue left toward the former ferry terminal and now the DEC Public Boat Launch. As you continue along the shoreline into Powerhouse Park, the rough terrain is all that remains of a power plant.

The shoreline here has drastically changed. Originally it was much closer, but over time was filled in with waste tailings. Lakeshore sands in Powerhouse Park and the municipal campground are the waste product of years of iron production.

If you drive left down Tunnel Avenue, you’ll see the remains of worker housing. At the north end of Tunnel Avenue, are the remains of the earliest iron industry-related building in Moriah, a stone casting house—though it may require some imagination to recognize it. When the railroad came through in 1875, Bay State Iron Company had closed, so right of way was no issue. North of the site, however, steep cliffs rose directly out of the waters of the lake. So a tunnel was cut through the bluff from here to Craig Harbor. Today, the railroad runs at the edge of the lake, on a bed of rubble that blocks the outlet of Craig Harbor Canyon.