Andebit et beaqui corendit, ut quostes esciendion re dit ad et prae parion es quia quas alibus sam, omnim faciden ducipidiat arum autem nobis enis es voat

14. The Invisible Town of Fletcherville

A Furnace Builds a Town

Listen to the Site 14 Audio Narration of the Iron Story

Another hamlet that lived and died with the iron industry was Fletcherville. Fletcherville, like Hammondville, is a testament to the drive and desire of the entrepreneurs and capitalists who looked upon the Adirondacks wilderness and saw nothing but assets and opportunity. And like other small mining towns, these towns would never have ever come into being—much less prospered—without iron.

Today, the once-booming town of Fletcherville has been swallowed by the landscape. The site of Fletcherville has faded from the landscape—now an overgrown forest—but its significance to the iron industry in Essex County has not.

Fletcherville was one of two exclusively Irish communities. (The other was Cheever.) It had a short life. In 1863, during the peak of prosperity, the Witherbee’s formed a partnership with Friend P. Fletcher of Vermont.

On Lots 48, 75, and 107 of the Cheever Iron Ore Tract, Fletcher owned 4,000 acres of high-quality timberland, beneath which was, of course, a bed of magnetite iron ore. Fletcher formed a partnership with Silas H. and Jonathan G. Witherbee and together they built what would be the last charcoal-fueled blast furnace in Essex County. The Witherbees and Fletcher chose a local man with many years’ experience in the iron industry to build the furnace at Fletcherville.

Jerome B. Bailey’s career in the iron industry began in 1829 when he was superintendent of the Peru Iron Company in Clintonville. Except for two years when he was briefly in the employ of the Ausable Iron Company, Bailey remained in Clintonville until 1851. He oversaw the building of the Fletcherville furnace from 1864 to 65.

There was no source of moving water at Fletcherville, so, like Colburn Furnace, Bailey’s furnace was steam-powered. The furnace was 42 feet tall and made of quarried granite. The steam engine in the adjacent boiler had a 64-inch blast cylinder and a 24-foot-wide flywheel. The blast which was first blown in in August 1865 soon became a 24-hour process. For every ton of iron produced, 223 bushels of charcoal were required, according to Thomas F. Witherbee. The furnace had ten rectangular charcoal kilns, an improvement on the older beehive design, each one able to process 65 cords of wood for making charcoal at a time. (See Learn More: Making Charcoal)

The people that worked the furnace, turning out nearly seven tons of pig iron a day, needed appropriate accommodations. This was what transformed the furnace site into the hamlet of Fletcherville. Boarding houses and a company store were soon built to accommodate the workmen and their needs. Some men brought their families so more appropriate homes were built along the road. It was rumored that the men drank a gallon of whiskey for every ton of iron they produced, so a saloon was most likely also built.

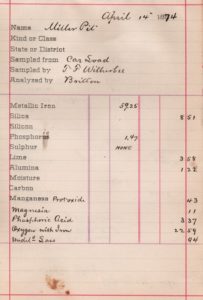

When Jerome Bailey left the operation in 1869, Thomas F. Witherbee succeeded him. Thomas, the younger brother of Jonathan G. Witherbee, was a founding partner in what would become one of the major iron operations in the Mineville area—Cedar Point Iron Company. Thomas was born in Port Henry on October 10, 1843. He attended Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute before leaving in 1862 to enlist in the army. He received an honorable discharge in 1864 and returned to Port Henry, working as Bailey’s assistant at Fletcherville. After Bailey left, Witherbee continued making improvements to the furnace. An innovator who gained national recognition, he added 20 feet to the height of the stack, making it 62 feet tall. He also established a chemical laboratory at the furnace to analyze and control the product. It was one of the first labs to be opened at a furnace operation for that purpose. As the surrounding forests disappeared, he was one of the first to begin substituting anthracite coal for charcoal as fuel for the blast process.

The furnace was an innovative operation. Fletcher and an associate from Vermont, V.W. Blanchard, developed a new gas jet method for reducing molten iron to an atomic state, even taking out a patent for the process. However, there is no record of the method having been tried at Fletcherville.

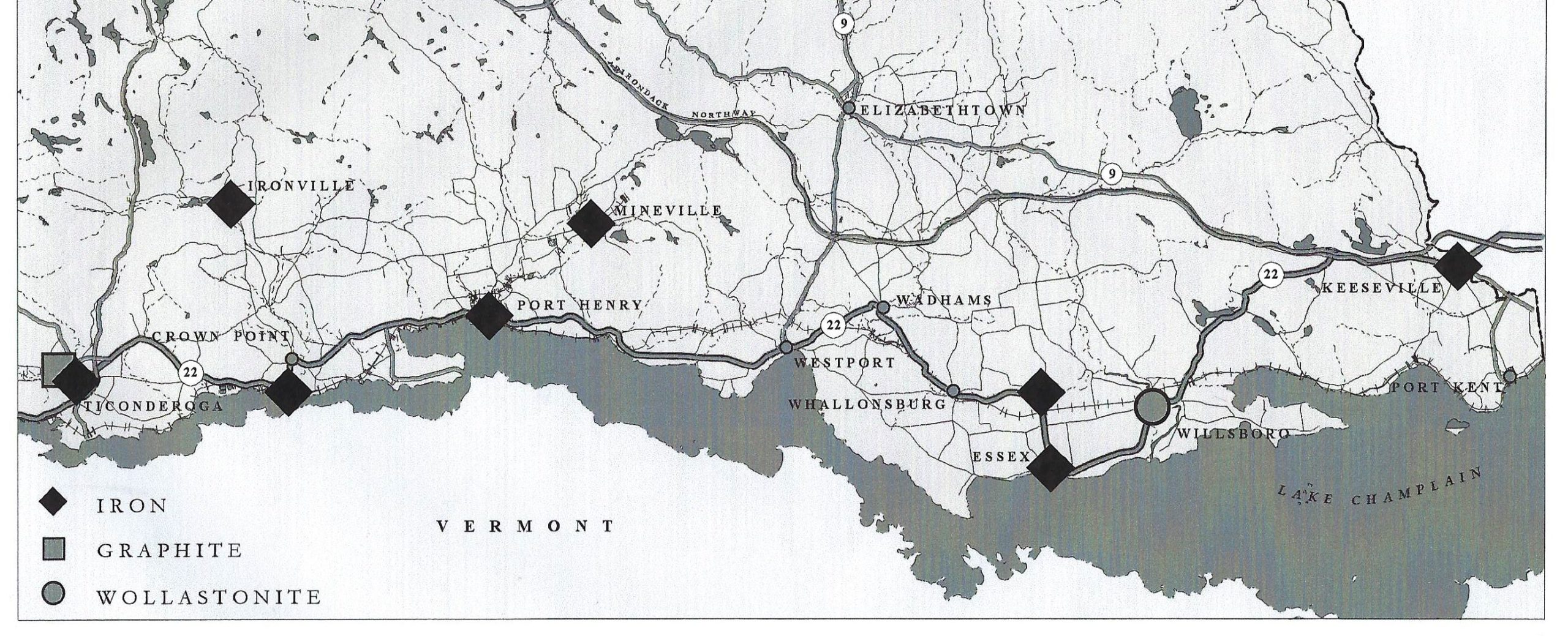

The Fletcherville furnace operated successfully for nearly ten years, sending well-suited iron to the firm of Griswold, Winslow and Holley in Troy where it was used in one of the earliest Bessemer steel plants in the United States and made into railroad tracks. The pig iron that came out of Bailey’s furnace was shipped to other lower Hudson River Valley forges and furnaces to be made into horseshoes, artillery, and other military machinery and war materiel. Fletcherville iron was also shipped to the ironworks at Clinton Prison in Dannermora and nail works in Keeseville and Ausable Forks.

When the Lake Champlain & Moriah Railroad opened in 1873, it made transportation of pig iron to canal boats on the lake and eventually the Delaware & Hudson Railroad to Troy even more efficient. It seemed that Thomas Witherbee had the Fletcherville operation heading in the right direction. Yet despite innovation and the high quality of iron, economic factors were simply not favorable for Fletcherville iron. A severe drop in the price of iron from 60 to 30 dollars a ton in the early 1870s contributed to the early demise of the furnace. With the deaths of Friend Fletcher in 1874 and Jonathan G. Witherbee the following year, the Fletcherville furnace shut down. Many of the workers who had called the now-invisible hamlet home left to find work elsewhere. Others—with little options—stayed. Local historians note that food was sent to the “starving people of Fletcherville” in the 1890s.

Reverend Smith, a local historian at the turn of the 20th century made the following observation just ten years after Fletcherville was abandoned: “Surely a more desolate place cannot be imagined than this ruined mining settlement, lying high up in the mountains, where the soil is thin and poor, and where the trees have been cut off for miles around, burned to feed the great furnace which is now but a heap of shapeless ruin. Time has veiled the hillsides with thick, slender second-growth timber, but the village houses still stand unshielded upon the bare slopes.”

Travel Tools

Drive east on Broad Street until you reach the T with Fisher Hill Road. At this intersection across the street is Raymond Wright Park, which you can take a detour to. Otherwise, turn left onto Fisher Hill Road and continue. (Fisher Hill Road will eventually become East Lincoln Pond Road.)

Fletcherville would have been in the wooded hills off the Bartlett Pond Road–but trees and time have erased any visible evidence.

Driving north, just before the water tower, you will pass the Moriah Shock Camp Prison on your right, which is an example of a mining building that has found new life. Its area was once the site of the Fisher Hill Mine (run by Republic Steel). Republic Steel decided to develop the Fisher Hill Mine in 1941 as part of the war effort, which demanded tremendous amounts of iron. The facility was designed to handle 8,000 tons of iron ore per day.

Detour: Raymond Wright Park

Detour: Hike the CATS Mountain Spring Road Trail, which runs through what was the town of Fletcherville.