Andebit et beaqui corendit, ut quostes esciendion re dit ad et prae parion es quia quas alibus sam, omnim faciden ducipidiat arum autem nobis enis es voat

13. The Heart of Mineville

A Company Rules the Town

Listen to the Site 13 Iron Story Audio Narration

From 1885 to the early 1890s, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute students of iron-metallurgy, led by Professor Henry B. Nason, traveled from Troy to spend several days touring the mining and refining works at Crown Point, Port Henry, and Mineville. The senior trip was a unique learning opportunity for the students., but the enthusiastic young men also used the occasion away from school to have a good time. Mineville was a prosperous town in its day. By looking at the buildings today, it’s possible to get a sense of the importance and impact of this industry and of how both mine workers and company owners lived. For more than a century, mining dominated this landscape. Yet, much is now abandoned.

Headquarters for Witherbees, Sherman & Company were in Mineville, although they also had an office building in Port Henry. At the top of the hill is the 1907 neoclassical office building. Most of the long, concrete stairway is no longer there, but elements of temple-like grandeur are still evident. Perched on the side of a small hill, it held a prominent location, a vantage point from which much of the mining operations in the local area could be seen: mine shafts, mills, railroad lines, company housing, and workers. Like other company buildings, the office is made primarily of concrete blocks. Republic Steel used this building as its headquarters when it took over the operation in 1938. It is now a private residence.

The white buildings directly to the east of the company headquarters comprised the company-built hospital. It was certainly the site of plenty of grisly surgeries, amputations, and other procedures to deal with the numerous injuries that took place in the mines.

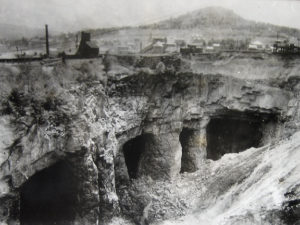

Adjacent to the former office building and a hospital is the #21 Mine, now fenced in and posted—though a peek between the trees reveals the enormous magnitude of the open pit.

In 1875, Mineville accounted for 8.8% of the 2.5 million tons of iron ore mined in the entire United States. Thirty years later, these same mines, with the application of improved technology, were yielding three times as much ore. Even with this dramatic increase, it was still only a tiny percentage of the national total of 50 million tons of ore. When Frank S. Witherbee wrote his compendium history of the iron companies of Essex County in 1906, he stated that 13 million tons of ore had been mined up to that time. “Perhaps,” he said, “the most graphic way of expressing this tonnage would be to state that it would make a solid freight train stretching from Port Henry to beyond Denver, Colorado.”

Sitting below, across the street, stands Memorial Hall. This shingle-style community building was built in 1893 by cousins Walter and Frank Witherbee to honor the memories of their fathers, Silas and Jonathan Witherbee. Today it is home to Veterans of Foreign Wars Post 5802. The elementary school and high school once stood on each side of the building. Behind Memorial Hall, now looking like an overgrown gully, was another center of operations that was home to several mines.

Witherbees, Sherman & Company reincorporated in 1900 when Lackawanna Steel Company from Buffalo bought George R. Sherman’s one-third interest after he died in 1895. It was then that the company dropped the “s” and became simply Witherbee, Sherman & Company. The 1893 financial panic had a major impact on the iron industry. Witherbee, Sherman also encountered business difficulties in the early 1900s. Two major destinations for ore in Troy: Burden Iron Company and Troy Steel and Iron Company were both struggling to stay in business. Refining was now centered around Pittsburgh and U.S. Steel, and the Lake Superior ores, especially the Mesabi Iron Range in Minnesota, was the most economical. Witherbee, Sherman attempted to find a company that would buy its entire interest, entertaining offers from Standard Oil and Bethlehem Steel. Witherbee, Sherman continued mining, but the numbers began to dwindle. Not until Republic Steel’s purchase of the entire Witherbee, Sherman operation in 1938 was a company able to work the mines to profitability as they had been during the 19th century.

Travel Tools

From Route 6 (Broad Street), drive up Hospital Road to the promontory of the former Witherbee, Sherman Headquarters (27 Hospital Road). The white buildings next door were all part of the hospital. And directly below, across the street is Memorial Hall, which was an employee social center and now serves as a VFW post. A high school and elementary school—long since razed—flanked Memorial Hall. The Iron Center Museum in Port Henry includes a scale model of the entire complex. Afterward, you’ll continue east on Broad Street.

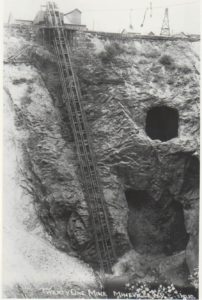

First-Hand Accounts

Descriptions by Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute students of Mineville and the mining process: “Mineville is the place where the ore (principally magnetite) is obtained and sent to the furnace. It is a very pure ore, containing nearly seventy per cent. of iron, and there are several shafts leading to pockets where it is worked. The large mine is an enormous hole nearly 400 feet in depth, but as portions of the roof were falling at intervals, it was not considered safe for us to descend. We were told that one side would be sure to cave in in the course of three months. We descended another shaft, however, going to the depth of 350 feet, and watched the process mining. One of our number here met with the only accident which occurred on the trip, falling into a hole about six feet deep, and bruising his face and hands. Part of the class walked up the entrance instead of being hoisted in the bucket, there being a stairway of 250 steps to the inclined plane which led into the depths of the mine.” – The Polytechnic, October 24, 1885

“The mines at this place formed an interesting feature of study, and the fine hoisting machinery was a revelation to many. The descent into some of the mines was an exciting trip, which to uninitiated, did not seem to be entirely devoid of danger. The scene in the mines, however, was well worth the trip. The electric lights made the shadowed portions only more intense, while in its full glare, the particles of magnetite glistened like diamonds.” – The Polytechnic, October 30, 1886