Andebit et beaqui corendit, ut quostes esciendion re dit ad et prae parion es quia quas alibus sam, omnim faciden ducipidiat arum autem nobis enis es voat

22. Driving Route 22 South to Cheever

The Pride of Baseball

Listen to the Iron Story Site 22 Audio Narration

Cheever iron ore was first mined in the 1700s by Philip Skene, then Benedict Arnold, and in the 1800s by James Dalliba. After Dalliba, the bed went through several owners. Aside from being one of the first sites of iron mining, it was also one of the first iron ore beds worked profitably in New York state. A settlement developed around the Cheever mines as commercial mining was becoming a serious business. You can see remains today driving south on Route 22, in what might appear to be a random cluster of homes. A NYS Marker identifies the location as the site of the first blast furnace along route 9N in Moriah.Dalliba constructed Moriah’s first blast furnace about three-quarters of a mile south of the Cheever mine, near the lake. (A historical marker marks the spot, along the east side of Route 9N.)Although the charcoal-powered furnace produced only 15 to 18 tons of iron per week, it signaled the beginning of serious iron mining in Moriah. The pig iron produced in this furnace was shipped to Troy. Dalliba’s presence in what would become known as Port Henry inspired a new phase of settlement in the northern part of Port Henry. In 1827, the Dalliba furnace was converted to a stove and hollow works—the first foundry in New York State. Following Dalliba’s death in 1832, the plant was upgraded and a new furnace was built closer to the lakeshore at what’s now called Powerhouse Park in the northern part of Port Henry. Its 1854 furnace was notable because it was the first in the area with an iron chimney stack. At least three more furnaces followed.Unlike Witherbee or Mineville or Ironville or Hammondville—or any other mountain mine, Cheever had an advantage. Cheever Mine was ideally situated by the lake for shipments by water to the furnaces at Port Henry, and beyond. When the main line of the railroad passed by the Cheever dock, the mine had economic shipping by both rail and water. Between 1852 and 1884, the Cheever bed produced 50 to 60 thousand tons of ore per year.By the 1860s, Cheever was a proper settlement not unlike Hammondville or Mineville, with largely Irish immigrants who had arrived in the 1840s.Former resident Daniel Murphy may have taken some freedoms when he described Cheever life in the mid-1800s: He claimed an air of discipline hovered over the place. Life in Cheever was tranquil and secure, according to Murphy, who wrote in his diary:

“At Cheever, there was no real need for a law officer, for the employable people, as a rule were quiet, of steady habits, reliable, trustworthy and not given to excesses of any kind. Residents never for a moment thought of locking their doors, day or night. As to drunkenness it may be said, there was none at Cheever, except for one old timer, who otherwise was the salt of the earth.”

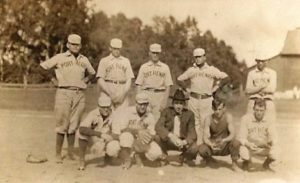

Murphy claims the children were well educated in Cheever, as were the working men. In an effort to break the language barrier against which immigrants struggled, an adult education program was approved by Superintendent John O. Presbrey, saying to program sponsor Duncan Thompson: “I heartily approve your suggestion and recommendation. This is a worthy cause and justifies the expense. Go ahead. Teach them reading, writing, and arithmetic and convert those men into good citizens.” The men of Cheever were never persuaded to strike, though the miners from Moriah marched on Cheever in hope of riling them to action, claims Murphy. Labor organizations didn’t enjoy much success during the 19th century in Crown Point or Moriah. Even though Moriah miners attempted to coerce the Cheever workers to strike in sympathy, like the Hammondville strike (See Learn More: The Panics and Swedish Labor Strife), an activity like this was generally resolved incident-free. According to Murphy, it would seem that families were lucky to live in a place like Cheever during the 1800s, where life was pretty close to ideal.Whether or not you take Murphy at his word, one thing is for sure, the men of Cheever channeled their energy into proving themselves in baseball. Nowhere was community pride more evident than on the baseball fields. Baseball was first played in Port Henry in the 1860s. A Port Henry baseball club at the time was known as the “Minerals.” A club at Mineville was named the “Emeralds.” In the 1860s, writes Murphy, the Moriah Ionics made short work of the teams from Port Henry, Crown Point, Whitehall, and Ticonderoga.This inspired the men of Cheever, writes Murphy: “The earnestness and expertness displayed by those rival baseball teams on this occasion stirred up the sporting instinct of the elder Cheever young men to a man determined to devote more time to practice the game and to this end beat a well-worn trail over the mountain to the clearing opposite Connor’s farm where sides were chosen at every practice so that in competition the players in the best form would represent Cheever. And this with the definite purpose of eventually trying to dethrone the ‘Ionics’ of Moriah.”

There were several teams in Crown Point and Moriah during baseball’s wildly popular early days. The team names may have changed over time, but the rivalry and fan loyalty remained strong. Some of the teams included the Hammondville Bessemers, Port Henry Wagon Washers, Moriah Iron Ore Eaters, and the Cheever Ocean Waves.

It was also one of the few times, when different classes, company hierarchies, and nationalities interacted socially. Teams included office workers, miners, furnace men, local merchants, and others. Mining companies often furnished equipment and sponsored fields. In 1886, RPI students, while on a field trip to learn about the mining operations, played a baseball game against the Port Henry team—and lost. In fact, one student wrote, they were “demoralized” by the local team. In his book, Through the Light Hole, Patrick Farrell described baseball’s popularity: “In this period before easy distant travel [pre-World War I] attendance at baseball games drew large crowds…a three-game series between Mineville and Port Henry at the Westport Fair drew such large crowds that it was difficult to keep the infield clear of spectators. Betting was heavy…”

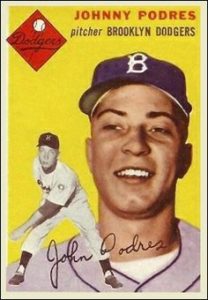

At Cheever, games were played in the north of the village, on the property of the Bay State Iron Company, on a level plateau called “Foote’s Meadow.” (Foote’s mansion still stands today—though in greatly changed form—overlooking the lake.) At some point, the baseball field moved to a meadow located near Cedar Point in southern Port Henry, with teams visiting from Plattsburgh, Ticonderoga, Westport, and elsewhere. That legacy continued. Left-hand pitcher Johnny Podres, a native son of Moriah, played a major role in the historic Brooklyn Dodgers 1955 World Series victory.

Like other small mining towns, Cheever didn’t last long. By 1883, the community of 60 tenements lay mostly empty. A journalist writing in the Plattsburgh Morning Telegram in November 1883 described the scene: “The failure of obtaining more ore at Cheever has cast a gloom over that place… The running of a large amount of machinery, the clanging of the drill, the rolling sound of transporting cars, the jar of dumping vehicles, all have ceased, and today Cheever is a deserted village. Tenement homes are discovered empty, dismantled, and forlorn. Their occupants have wandered away from their homes, seeking some other point where they can gain a livelihood. A death-like presence prevails; dismantled houses are the rule.”

The journalist continued, writing that just a few years earlier, Cheever was a prosperous village, bustling with activity. “But how great the change! They of the willing laborers who are here are the sad-eyed men one meets upon the streets… They who remain, remain because of want of sufficient means to depart. It is a melancholy counting of the results of a miner’s life. The saddened men and wives…tired…their only prospects are poverty.”

Despite the grim description of this contemporary journalist, many were able to move on. A significant portion of the Irish miners, along with second-generation Irish merchants who provided services to the Cheever community, went to Witherbee and Mineville. Many of the miners would become managers for Witherbee Sherman, and occupy some of the nicest company housing, which would be built in the first decade of the 20th century. A few of the merchants would establish branches of their Port Henry stores in the rapidly expanding residential community of Mineville, providing goods to the new waves of Italian and Eastern European immigrants.

Travel Tools

After turning right (south) from the Pilfershire Road onto Route 22, you’ll notice a cluster of buildings. This is what remains of Cheever. Rust stains on the cliffs on the lake shore alerted people to the presence of iron ore, which was mined here before the Revolutionary War. A painting, reproduced in an exhibit at the Iron Center in Port Henry, shows the mine just after the Civil War, when production had halted. Further south, you’ll see a sign for Bay State Furnace and Cemetery. This flat land between the highway and the lakeshore was the site of Bay State Iron Company for several decades, beginning in the 1820s.

First-Hand Accounts

The then-owner of the Cheever mines, Oliver Presbrey, tried to find capital investment in the 1880s and 1890s—without success. In 1893, the year iron demand fell drastically in the United States, Presbrey wrote to the Witherbee Sherman Company: “I have all but closed a contract with Penna parties, for my output for 1893, but find that I will be obliged to cut prices on “Lake Champlain” ore, in order to introduce Cheever ore into an entirely new field. I should be glad if you could handle this ore in such sections as might require an ore lower in phosphate than that from “21” and thereby obviate the necessity of my making my prices below yours.” But he was unable to find enough people to work his mines, part of his property was vandalized, and he completely closed his operation that same year. -Letter from Oliver Presbrey to Witherbee and Sherman (in Rosenquist, The Iron Ore Eaters, pp 24-25)