Andebit et beaqui corendit, ut quostes esciendion re dit ad et prae parion es quia quas alibus sam, omnim faciden ducipidiat arum autem nobis enis es voat

27. The Cedar Point Iron Company

Trying to Keep up with Technology

Audio Narration of the Iron Story site 27

When operations at Fletcherville ended because charcoal furnaces were no longer feasible due to drastic deforestation of the Adirondacks, Silas and Jonathan Witherbee and George R. Sherman spearheaded the formation of the Cedar Point Iron Company in 1872.

Thomas Witherbee was put in charge of the new furnace. Incorporating his experiences gained while at Fletcherville and as an RPI student, he oversaw the construction of the Cedar Point furnace and served as ironmaster for more than a decade. He also introduced the latest in furnace design nationally: For example, he installed the first Whitwell firebrick stoves ever erected in this country, importing the brick and castings from England. He also invented a few innovations of his own. He recorded his ideas for plant improvement in technical papers for the American Institute of Mining Engineers. The site also included an anthracite coal furnace.

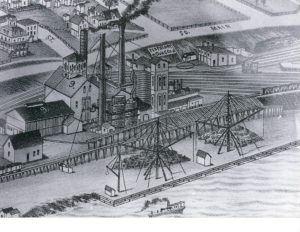

The docks at Cedar Point were built with a series of overhead tracks which allowed the dumping of ore into stockpiles into various bins along the waterfront. By 1875, there were five tracks here, laid side-by-side to accommodate the endless line of ore cars coming down from the mines

When the modern blast furnace was completed at Cedar Point in 1874, it changed the shoreline of Port Henry. Ten blast furnaces had operated in various earlier locations throughout Moriah, but the Cedar Point Furnace was the first to rely on cheap rail transportation down from the mines to the lakeshore and points south. (The Moriah Lake Champlain rail line was completed that same year.) Over 45 years, Cedar Point furnace increased production from 41 tons to 250 tons of pig iron per day. Stacks of pig iron would await shipment in the furnace yard.

The furnace was built at a cost of $600,000, but the economic downturn prompted by the Panic of 1873 prevented it from going into blast until August 1875. It produced 26,000 tons of pig iron every year. Witherbees, Sherman & Co. was closely associated with its operation although the company did not take complete control of it until 1885. It was first leased to Slayback, Robinson and Company from New York, which added a Clapp-Griffith steel plant to the facility in hopes of introducing the latest technology for making steel. A group of RPI students visited the furnace in 1886 and wrote about their disappointment that the Clapp-Griffith steel plant was not working:

“…the furnace at Port Henry was visited, and we were also interested in examining the Clapp-Griffith steel plant. We were sorry not to see this latter in operation, as it is one of the few outside of Pittsburgh. The process does not seem to be a success at Port Henry, as it was only in operation for six months.”

The efforts to introduce this new steel-making process in Port Henry suggest that local iron industrialists were attempting to keep up with the latest technology–a technology that was supposed to revolutionize the iron industry as a “rival of the Bessemer process.” It would decrease the number of high-skilled laborers (puddlers), and allow for the use of low-cost, high phosphorus ores. Although it is not clear why the Clapp-Griffith plant failed in Port Henry, it was eventually moved to Pittsburgh, which already was becoming the new center for U.S. iron and steel operations.

Until 1887, Thomas Witherbee remained in charge at Cedar Point, where his achievements were nationally recognized. He then went on to Durango, Mexico, as superintendent of a large ironworks. He later managed furnaces in Chicago and Wisconsin, and eventually went back to Durango, where he remained until his death in 1909.

In the early 1900s, the Cedar Point furnace was leased once again, this time to Pilling & Crane of Philadelphia. This was a Frankenstein’s monster of a blast furnace, having had an engine from a Bay State furnace added to it to increase its blowing capacity and several hot blast stoves from the former Crown Point furnaces, which helped increase the furnace’s output to 175 to 200 tons of iron per day.

A second blast furnace was built there in the 1920s, further increasing iron capacity. At the time, this area would have look similar to an industrial hub of Pittsburgh. In the 1930s, the Port Henry shoreline was extended out into Lake Champlain by several hundred feet using tons of tailings. This was the site of Republic Steel Mill #6 that went into blast in the summer of 1940. When Republic Steel closed the mines in 1971, its facilities were mostly demolished. Mill #6 was removed from the shoreline and the elevated trestle leveled. The only building left is the concrete block warehouse made from tailings, which is now used by the marina. If you look carefully, you might be able to see the rail lines and lights in front of the double doors of the structure.

A second blast furnace was built there in the 1920s, further increasing iron capacity. At the time, this area would have look similar to an industrial hub of Pittsburgh. In the 1930s, the Port Henry shoreline was extended out into Lake Champlain by several hundred feet using tons of tailings. This was the site of Republic Steel Mill #6 that went into blast in the summer of 1940. When Republic Steel closed the mines in 1971, its facilities were mostly demolished. Mill #6 was removed from the shoreline and the elevated trestle leveled. The only building left is the concrete block warehouse made from tailings, which is now used by the marina. If you look carefully, you might be able to see the rail lines and lights in front of the double doors of the structure.

Travel Tools

Driving south on Route 22, turn left at the sign for Van Slooten Harbor Marina. Stay left at the V. All that remains of the huge Cedar Point Blast Furnace and Foundry, which produced 200 tons of iron per day in 1892, is the concrete block warehouse, now used by the marina. As you cross the railroad tracks, the land around you would have been underwater 100 years ago. At the time, the track traced the shoreline of Lake Champlain. Before Cedar Point Furnace was built, the natural shoreline lay close to the road, as it still does south of McKenzie Brook. About 1,200 feet of railroad trestle ran over the water from the Cedar Point furnace. The shore was extended several hundred feet east of Cedar Point as slag from furnace operations was dumped into Lake Champlain. At this now-quiet marina, you would have seen several furnaces, scorching, smoking, and blazing the night sky.

First-Person Account

RPI students writing about Cedar Point Furnace: “We found the workmen very obliging, and were shown all through the works, our knowledge of ballast furnaces being materially increased thereby. The furnace itself is 67 feet in height, and was running in full blast, producing about seventy tons of pig per day… The heat, of course, is derived from the gases brought down from the top of the furnace, a portion being carried over a building opposite the furnace, and burned there to produce extra heat for the machinery… We could almost imagine ourselves in the infernal regions when the ball which closed the top of the furnace was lowered, and the flames and burning gases shot up to a height of fifty feet, with a roar like the muttering of thunder.. We next visited the engine room and inspected the blowing engine, that being an immense one of 1,200 horse power and an eight-foot stroke. It is a surface condenser and has an adjustable cut-off, which is quite a benefit. The air pressure was between five and six pounds when we saw it, and the engine was taking twelve strokes per minute. This gives a sufficient blast for all ordinary purposes. At about nine o’clock the ‘cinder’ or ‘slag’ was run off, the molten river lighting up the whole place, and a few minutes after ten the furnace was ‘tapped’ for the iron. The scene of the swarthy men moving around almost in the midst of the fiery mass rushing out of the furnace, directing its course into the moulds, the dark night outside, and the almost unearthly brightness within, tended to cause one to feel awed and impressed, and we watched the operation in silence, interested beyond measure. At length the molds were full and from the tap-hole there came forth a sheet of flame, instead of the liquid stream before. Soon the hole was blocked up, the iron in the mold and sank into a dull read heat, and the operation was over.” – The Polytechnic, October 24, 1885

As iron industry declined, so did the towns around them: “The negative impact of the iron industry’s drastic decline after 1885 was far-reaching in a region whose economic base was very narrow and had long been heavily dependent on the iron industry. The great prosperity was abruptly replaced by economic crisis in many areas…. Iron towns as a group decreased 26.1% between 1880 and 1930 in marked contrast to an 8.6% population gain in non-iron towns.” -Geographer John Moravek, 1976